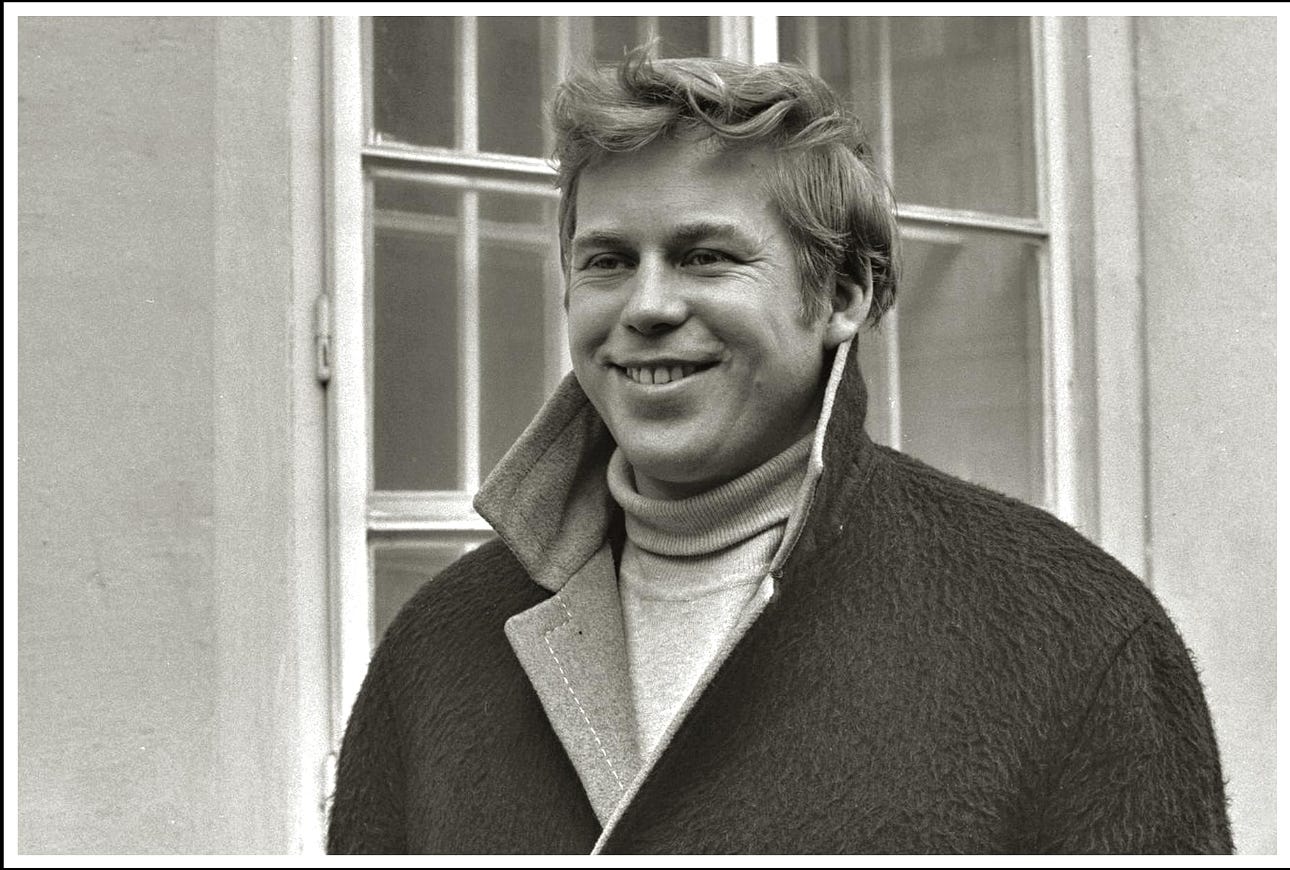

Václav Havel: Dissident Extraordinaire

Václav Havel was many things - a bourgeoise poet, an absurdist playwright, a committed chain-smoker, an employee of a brewery founded in 1582, defender of a psychedelic-rock band named ‘The Plastic People of The Universe’, and an anti-communist dissident to whom Samuel Beckett's dedicated his short play ‘Catastrophe’ while Havel was imprisoned by the Communists.

Eventually he became the last President of Czechoslovakia; and after its dissolution - the first President of the Czech Republic.

After a lifetime of promiscuity (when he was released from jail in 1977, he spent his first weeks of freedom with a mistress) while simultaneously writing celebrated prison letters to his working-class wife Olga; our philosopher-king ended up marrying Dagmar Havlová - a beautiful film actress.

As a final badge of honour, Havel was heavily criticized by Žižek in his LRB essay ‘Attempts to Escape the Logic of Capitalism’ after Havel had stridently defended the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

Now, now...steady on delicate reader. I know in today’s world that is more than enough reason to ‘cancel’ Havel (the Czech communists have already tried and failed), so before you rush to judgement do remember that the choice in Yugoslavia was between a multi-ethnic plural democracy led by Muslim president Alija Izetbegović in Bosnia and a fascist, ethnically-cleansed state driven by the Serbian monster Slobodan Milošević.

Side-Note: If you want to know more please read this insightful Nation article by the ever-articulate Christopher Hitchens, who once at the end of a debate against Tariq Ramadan (an Oxford Professor and Grandson of Hassan al Banna, the founder of Muslim Brotherhood) was asked by a member of the audience: “Which would be the best country for a female/homosexual Muslim to live?”. Hitchens had replied:

"That’s fairly straight-forward. Bosnia-Herzegovina - a culturally Muslim, European, open & democratic country which was saved from obliteration by the power of United States, for which the US hasn’t received a word of thanks since".

Coming back to Havel- our favourite Czech dissident.

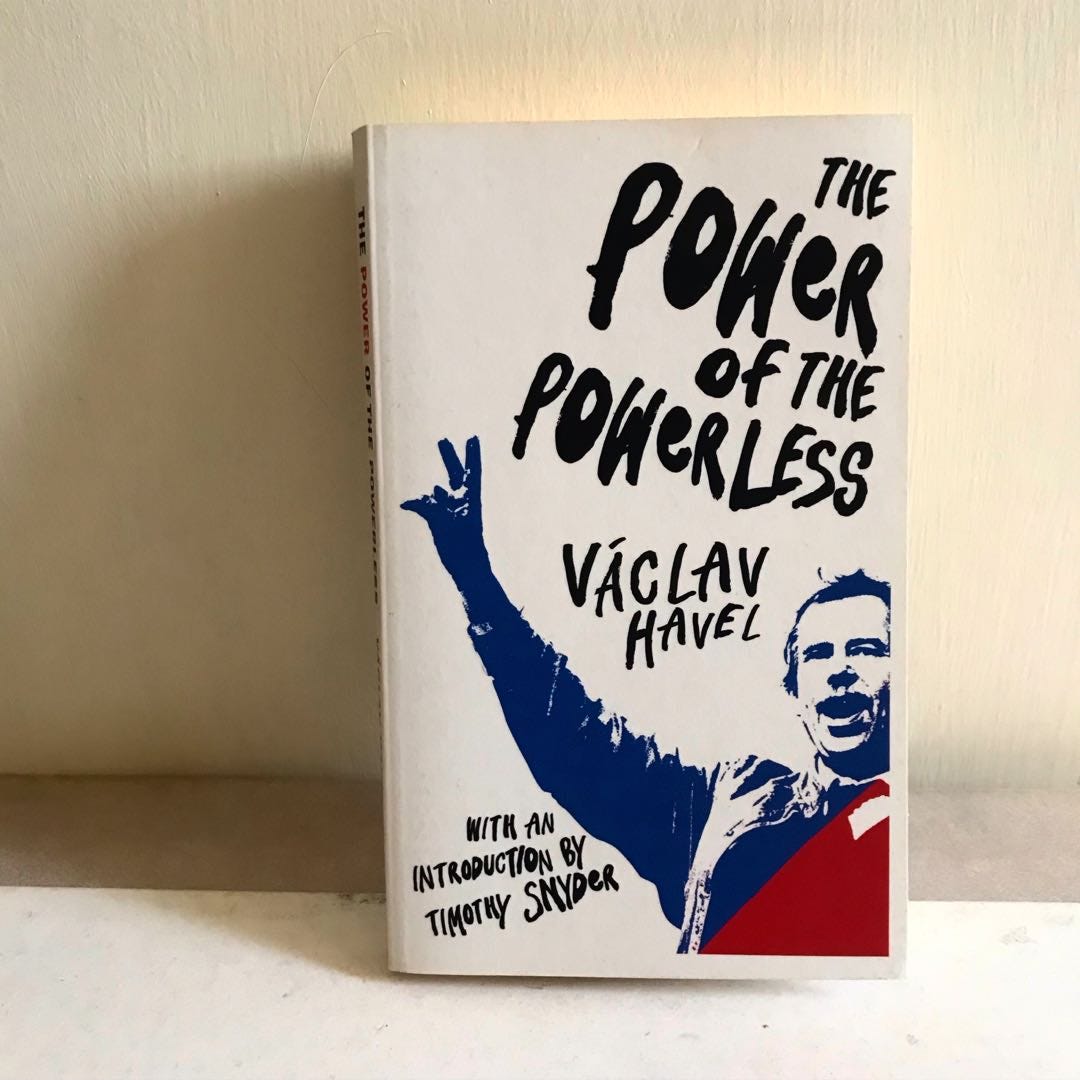

The reason for bringing him up is to wholeheartedly encourage every-one of you to read his 1978 essay - 'The Power of The Powerless’. Officially suppressed by the Communist State, the essay was circulated in samizdat form and translated into multiple languages- until it became a manifesto for dissent in Czechoslovakia, Poland and other communist regimes behind the Iron Curtain.

I do not exaggerate when I say that without reading this essay you can never fully grasp the idea of how power and ideology function in our modern world. When Havel describes the omnipresence of a totalitarian automatism where appearances have wholly replaced reality- I cannot help but find striking resemblance to the world we inhabit today, albeit with a different zeitgeist.

Perhaps the most memorable part of the essay is his dissection of loyalty and obedience to power when he writes:

The manager of a fruit and vegetable shop places in his window, among the onions and carrots, the slogan: ‘Workers of the World, Unite!’ Why does he do it? What is he trying to communicate to the world? Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world? Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals? Has he really given more than a moment’s thought to how such a unification might occur and what it would mean?

Obviously the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit; he does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses. This, of course, does not mean that his action has no motive or significance at all, or that the slogan communicates nothing to anyone. The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains a subliminal but very definite message. Verbally, it might be expressed this way: ‘I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.’ This message, of course, has an addressee: it is directed above, to the greengrocer’s superior, and at the same time it is a shield that protects the greengrocer from potential informers. The slogan’s real meaning, therefore, is rooted firmly in the greengrocer’s existence. It reflects his vital interests. But what are those vital interests?

Let us take note: if the greengrocer had been instructed to display the slogan, ‘I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient’, he would not be nearly as indifferent to its semantics, even though the statement would reflect the truth. The greengrocer would be embarrassed and ashamed to put such an unequivocal statement of his own degradation in the shop window, and quite naturally so, for he is a human being and thus has a sense of his own dignity. To overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on its textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the greengrocer to say, ‘What’s wrong with the workers of the world uniting?’ Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. It hides them behind the façade of something high. And that something is ideology.